Violence and Wars

28.08.2018

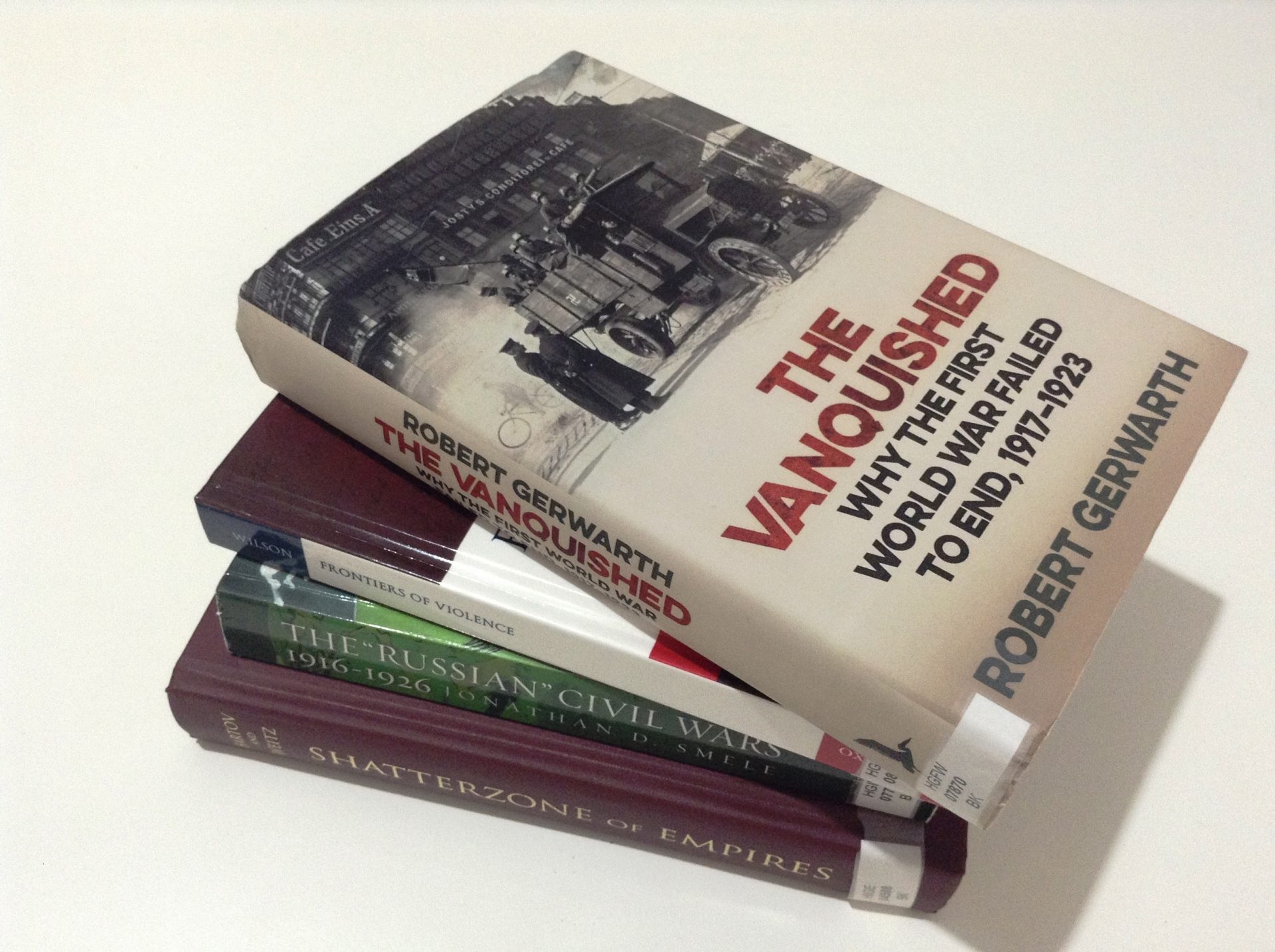

The centennial anniversaries of the First World War and the Russian Revolution evoked a new outburst of interest to the events in the East of Europe during the so called Big European Crisis of 1914–1923. Keeping track of the recent Anglophone publications, the Center’s library gathered one of the largest in Ukraine collections of new literature in English about armed conflicts, wars, and revolutions of the early 20th century. It must be noted that a large part of the publications are dedicated to events taking place on the territories of the present-day Ukraine.

Increasing number of publications on Eastern Europe during the First World War is not only the result of the centennial anniversaries but also of new turns in historiography. For instance, many researchers of the First World War departed from the Europe-centered approach which mostly referred to the studies of the UK, France, and Germany. Instead, historians focused on a global perspective of the war. While earlier, historians used to compare Britain with France, the collection of articles edited by Jörn Leonhard and Ulrike von Hirschhausen "Comparing Empires: Encounters and Transfers in the Long Nineteenth Century (2010) offers a broader comparative perspective. In particular, authors of articles compare British, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires. Besides, they are trying to overcome a conventional focus on the fall of empires. Instead, the authors suggest considering empires as "success stories." Another landmark publication of the recent years is the "Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands" (2013). It is, too, dedicated to empires and the interrelations between the imperial centers and the multinational peripheries. However, the "Shatterzone of Empires" edited by Omer Bartov and Eric D. Weitz focus not on the coexistence but rather on violence in the imperial borderlands in the 19th and 20th centuries. A number of essays therein explore local dimension of interethnic conflicts and their transnational perspective.

Another important group of books focusing on the East of Europe includes monographs considering the "East" of Europe in the context of causes and consequences of the First World War. The most notable in the group of studies is the book by Christopher Clark "The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914" (2012) and the one by Robert Gerwarth "The Vanquished. Why the First World War Failed to End" (2016). It is illustrative that the first book rethinks the beginning and causes of the First World War while the latter is an attempt to understand why the First World War "failed to end" in 1918. In "The Sleepwalkers," Clark shifts the focus from Germany as a key perpetrator of the war to all European states. Hence, according to him, the war was not started by a bellicose Germany but by all of Europe. Moreover, speaking against the marginalization of the events in the East, Clark emphasizes the important role of Serbia and the Balkans in escalating the conflict. The same as Clark, Gerwath focuses on the Eastern Front, too. Shifting the focus to the Eastern Front and the "vanquished" states make him conclude that in fact the year 1918 failed to bring any peace. On the contrary, new wars and revolutions led to another round of violence exceeding in their brutality the First World War in many respects.

In actual fact, the theme of violence that has always been overshadowed by wars and revolutions becomes central in current research. As such, the focus on violence allows getting beyond the imperial or national borders and viewing the processes in the East of Europe through transnational or supranational perspective. The Center’s collection has a peculiar corpus of essays edited by John Horne and Robert Gerwath "War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War" (2013). It covers the borderlands of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires and considers both separate national paramilitary groups and transnational networks and relations in Eastern and Central Europe, the Baltic states, and the Balkans. Authors focus not on the causes and consequences, but rather on violent practices and highlight their commonality in different parts of Europe. Another study concentrating on the interrelation between violence, imperial borderlands, and national projects is a monograph by T.K.Wilson "Frontiers of Violence. Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918–1922" (2010). In his book, Wilson explores violence in two regions, in Ulster during the Irish war for independence, and the post-war Polish-German armed conflict in the industrial Upper Silesia.

The theme of imperial borderlands and violence is also central for recent publications on the history of the Russian revolution. In particular, the works by Donald Raleigh "Experiencing Russia’s Civil War. Politics, Society, and Revolutionary Culture in Saratov, 1917–1922" (2002), Joshua Sanborn "Imperial Apocalypse. The Great War and the Destruction of the Russian Empire", Jonathan Smele "The "Russian" Civil Wars, 1916–1926: Ten Years That Shook the World" (2016), and the newly published monograph by Lora Engelstein "Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921" (2017) stress the importance of studying the regions in order to get an insight into the dynamics of the revolution and the civil wars in the former Russian Empire. Thus, Raleigh focuses on Saratov to illustrate that civil war was not merely a conflict between the White and the Red but a stand-off from different powerhouses, with strong centrifugal separation trends. Therefore, the fight also unfolded within the Bolshevik movement, while visions of the Center would often be not acceptable by the regional elites. The works by Sanborn and Engelstein show the importance of developments in the Baltics, in Finland, and in Ukraine. Whereas Smele emphasizes that collapse of the empire and civil wars in Russia cannot possibly be comprehended without accounting for the Central Asia context. In addition to geographical focus shift, historians also changed the timeline of the revolution and the civil war. Until recently, the research mostly has been limited to 1917–1920. Today, the study of the Russian revolution and war is not possible without accounting for the context of the First World War. At the same time, end of the conflict is not limited by 1920 but reaches forward to the mid 1920s.

Upon the whole, the books about the Great War, revolution, and armed conflicts of the early 1920s represented in the Center’s collection will be interesting not only to researchers of wars and violence but to anyone looking into the developments in Eastern Europe and within the area of the present-day Ukraine in the beginning of the 20th century. It is also important to mention that the collection is both methodologically motivating and easy and pleasant to read.

Review by Oksana Dudko

Credits

Сover Image: Center for Urban History